#7 | the specialty coffee price vs. the barista value

on the grassroots workforce of hospitality professionals, the barista best symbolizes the heavy workload, by function accumulation and diversion

this issue was translated by Luciane Maesp 📧 luciane.maesp@gmail.com

clique aqui para ler em português

As I write this first sentence, the 8.8 ounces coffee pack I usually buy at the supermarket costs US$ 2,85 (R$ 15, at the current conversion). Two or three years ago, it was half of this price. It is not an expensive coffee: it isn't organic certificated or fair-trade labeled. It's just an arabica from a market giant, with a well-known Brazilian coffee region name printed on the package. Between August 2020 and 2021, the commercial coffee market price increased by 37%, according to the Brazilian Supermarket Association (ABRAS). Even so, it costs around three times less than specialty coffee – the sort of beverage I would like to ingest every day.

Having coffee at a coffee shop was the thing I missed the most during social isolation. I've been living in Curitiba for ten years, and I can't count how many times I wrote or read the epithet "the Brazilian Seattle" as a reference to the reputed and high-quality coffee shops and baristas of the city. "Curitiba is that place where you're walking down the street and bump into a national champion," laughs the gastrologist Vitor Haubert, barista and partner at Manana Cafés, a coffee shop opened in November in downtown Curitiba.

And that's true, especially if you're in the expanded downtown area, where the main coffee shops are. Almost all of them opened in the mid-2010s when Curitiba began to pile up recognitions and awards – at the Brazilian Barism Championship, for example, most of the competitors were from Curitiba, and not hardly they figured on the podium.

In this short time, it's no overstatement to say that specialty coffee was the gastronomic product with the highest consumption growth and added value in Brazil. The understanding of coffee as a special beverage is relatively recent in the country: it happened in the late 1900s when we were the biggest coffee producer in the world, but not the best. From here, we were exporting the largest volume of commodity coffee bags, while neighboring Colombia was dealing with premium quality bags.

It's impressive what the coffee sector achieved in 30 years. In 2020, Brazilian specialty coffee production represented 15,6% of all coffee harvested in the country territory. Plus, in recent years, the value of this product has been rising, especially for exports. In 2021, 19% of the total amount of exported coffee was the specialty type, sold for 122 countries at an average of US$ 207,53 per bag (measure unit of 60 kilos).

Each pound of specialty coffee is worth two times the commodity one. In its producing line, specialty coffee requires more expensive inputs; more dedicated time; better-trained eyes; and comprehension of all the processes and principles that can develop that fruit into a complex drink. Naturally, the volume processed at a time is smaller, so that the human hands and knowledge can control the final result. In January 2022, a bag of Brazilian specialty coffee cost around R$ 1500, while commercial-grade coffee costs almost R$ 800.

— This added value accumulates in pockets other than the workers' – and baristas are one of the blue collars. I could talk about the Land Law of 1850; the three centuries of slavery; the importing of the cheap workforce; the land-grabbing; and the other institutional gaps and devices that set up and maintain the coffee production line. Yet, I chose to talk about the last end of this chain: the barista, the avatar of specialty coffee in urban daily life. —

Specialty coffee may be on the rise, but the barista is not. Its career is no different from other grassroots workers of the food business. As the cook and the waiter, a barista spends his six days working week standing on his feet to receive a category of work minimum payment of R$ 1,400 a month (about US$ 265 – just above the national minimum wage, which is far from providing a decent life). Even if he reaches a coordination position, his prestige will be greater than the value printed in his paycheck.

"Both the barista and the coffee shop are keeping the wolf from the door", says Ellen Krause, barista and certified instructor by the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA). Baristas are the professionals that most represent the precariousness that a customer service establishment stands on: they have to handle a series of activities that extrapolate their job description and responsibilities; the technical training is merely operational – but the knowledge that will make them stand out is frequently self-taught; and, on the top of it, these professionals often work in at least two different jobs or careers to be able to make ends meet. It's a fast-paced rhythm, and the irony is that caffeine stops kicking in after a while.

They should have a certain level of technical knowledge from the crop to the roast. The appeal for continuous improvement is much more empathic than what's expected from a line cook, as an example. However, a progression within the area does not necessarily relate to the accumulation of professional titles, such as roastmaster, instructor, and Q-Grader. These courses costs – in the beginner modules – are between R$ 1,000 and R$ 1,500, and may be carried out in just a few hours. That's a whole month's wage invested in one day.

Looking closely, most of today's well-established professionals got here due to a backlog of work – designers, journalists, and advertisers were the types I met the most in these almost ten years I've been working as a food journalism reporter –, without vacations, using their other jobs and freelance incomes to invest in the dream of the proper coffee1. It's a profession of enthusiasts.

Baristas are the professionals most exposed to unreasonable work demands, something quite naturalized in the food sector – aside from being a kind of individual speecher to every customer who sits at the counter, in between taking, preparing, and serving orders, cleaning tables, washing dishes, and charging the bill, it's possible that the barista still has to clean the bathrooms and the grease trap. "The backlog of work happens due to the size of coffee shops. Most of the time there is no way to hire more people because they are small businesses," explains Ellen.

Between being attendant and salesperson, the barista accurately and nimbly executes slow processes such as a filtered coffee extraction, while keeping an eye on the tables, heating a pão de queijo2, and washing the cups. "Some abilities we discover in practice. Being quick-witted, reading the customer's desire, making your latte art..." lists Ewerton Lemos Gomes, a graduated barista from SENAC3 course and Geography doctoral student. For five years Ewerton has kept the Tour CWB Coffee page on Instagram, with his partner Paula Hirano.

One can always ask, and the barista might be willing to answer about the coffee origin, its smell, mouthfeel, flavors, why does one or other method bring more body to the drink, which coffees have more acidic, how was that harvest, tips on improving your brewing at home, about the roasting process of that grain, which home grinder you should buy, etc. It's an endless list, so is the patience of many of them.

"We place the baristas who deal better with the public at the espresso machine at the counter, to let them talk with the clients, and shift to the filtered methods the baristas with great technique but not so skillful on the public attendance," reveals Ellen. The error rate of pulling an espresso in a machine previously adjusted by the senior barista is much lower than making a filtered extraction from scratch, which requires much more concentration and precision. That's a human resource allocation to optimize the client's experience.

The barista is a variable controller: time, temperature, grinding size, extraction method, weight, intensity, number of shots. To regulate the espresso machine, he needs to know about the coffee profile, grinds it in different sizes, pulls one, two, five, ten espressos at different times, until he finds the best recipe for that coffee batch. "Some coffee shops don't allow the barista to pull more than three espressos to adjust the machine. It's an 'economy' of coffee that doesn't make sense if you're pouring a special beverage," observes Vitor.

The qualification process of baristas is one of the most interdisciplinary of gastronomy – knowing by heart the terroir characteristics and the beverage notes are not enough, but rather understanding the principles of the transformations that the fruit goes to, what happens physically and chemically on these processes, besides having the scientific discipline to study on their own.

"I bought different methods and coffees to make my tests at home, so I could expand my repertoire," remembers Vitor. Empiricism is the barista's greatest teacher, and also his main asset. The more one can test and learn from the tests, the better he can extract coffee in different methods. "The school is the counter and the curriculum is the cup," summarizes Ellen, who, on her coordinator times, paid attention to the organization of baristas. "You gotta learn that washing the pitcher is the first thing to do after pouring an order," she recalls. A prerequisite to keeping the workstation clean and organized.

In one of the many notebooks I piled up over the years as a reporter, I sketched an infographic about the specialty coffee value chain while chatting with Maria Mion, barista, educator, and SCA-certified instructor. Four years ago, in the south of Minas Gerais state, at São Gonçalo do Sapucaí's heat, we drew paper while enjoying the porch of a house of Capadocia Coffee's farm. It was a flow sheet with icons and arrows, where the icons represented the raw material's stage and cost; and the arrows represented the percentage of added value inserted by human labor to the coffee: seeding planting, pest control, manual harvesting, drying, sorting, transport, warehousing, roasting, cupping, packaging, distribution, grinding, filtering, front of the house service, dishwashing.

The diagram started with the seeded plant and ended up on the cup of coffee. Unfortunately, this infographic never came out.

Even without the visual aid of this scheme, it's easy to notice that the coffee's added value comes from the worker's hands while the profits go to only a few pockets. The worker that manually selects and harvests the coffee is paid by the hour or on a contract basis; the farm owner, per bag; the roaster, by weight; the barista, by wage.

Most of the coffee chain professionals will never be able to pay periodically for the specialty coffee they produce.

For the barista, who has to drink specialty coffee as part of his good work, the value of the hourly wage is worth one espresso – precisely R$ 6,36 (or US$ 1,20), according to the category's labor union in Curitiba (Sindhotéis). A freelance barista in Curitiba earns between R$ 10 and R$ 13 an hour. "It's a wage that we've been trying to raise for years. During the pandemic, we gathered a group of baristas with the agreement of not working in coffee shops that would pay less than it. But that's not something everyone could choose about, unfortunately," says Vitor. At Manana, the work hour of a freelance barista is R$ 15, a value considered the minimum by the co-owners and partners Vitor and Dora Suh.

Some coffee shops pay below because there is a relative abundance of labor at this moment. Every three months, 20 fresh new baristas complete their 160-hour course at Senac, a workforce that can be readily absorbed for freelance work or the to-go coffees that multiply fast through the city. "A third of the course is theoretical. Everything else is you and the machine preparing and drinking dozens of cappuccinos," reports Ewerton. "The technical course prepares you to master times and movements: grinding, tamping, flushing, fitting the portafilter, making the extraction. The pre-infusion, brewing ratio, moves on the container to homogenize the essential oils of the drink. You repeat these movements until they become muscle memory, an automatic act," he adds.

On the proliferation of chains of self-service micro coffee shops, the customer faces queues for a cappuccino in a paper cup. With no dining room, few menu options, and staff training from scratch within the chain itself, the operational cost decreases. The moves and recipes taught are part of the business plan strategy to expand units and output a stable quality product, but with low sensorial complexity.

In a way, it is an unprecedented simplification that we're seeing in the third wave of coffee: the removal of the variables and making the barista's function merely operational. The first espresso machines created and spread in the early 20th century required the presence of a machinist able to understand that imponent steam-powered machine operation, which sometimes could explode because of the higher pressure. By the way, it's from the physics pressure measurement unit, bar, that the term barista comes from – oh, the irony!

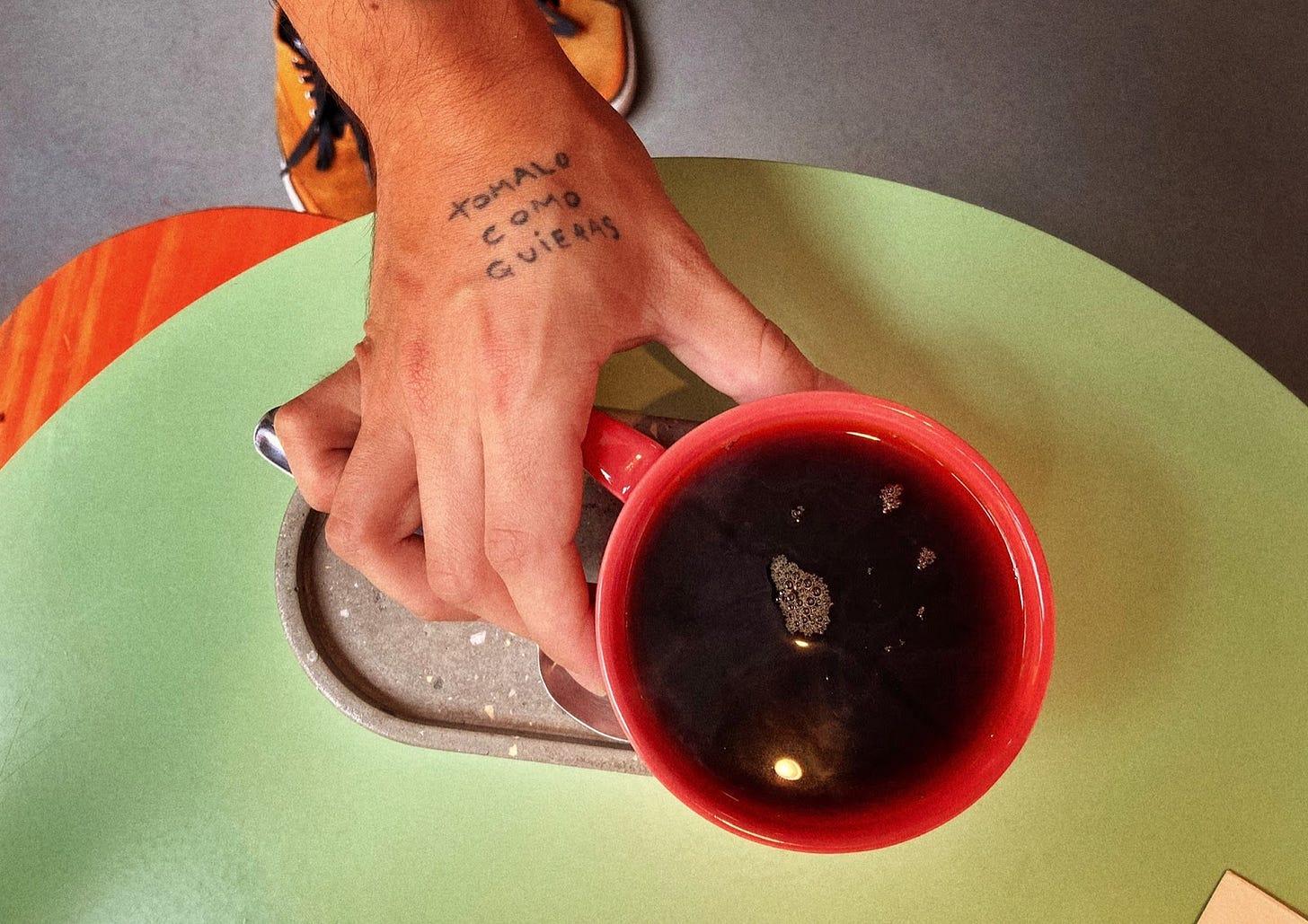

Between earning little and earning poorly, there's a trickling, but continuous movement of baristas who prefer to open micro-roasters to sell their own coffee brand or even a small shop to serve their short-menu specialty coffee at a fit4 value. On Manana Cafés's back wall there's an A0 size poster that reads:

trabajar menos

trabajar todos

producir lo necesario

distribuir todo5

Thank you Bruno Bortoloto do Carmo, Coffee Museum of Santos’s historian; Dora Suh, of Manana Cafés; Ellen Krause; Ewerton Lemos Gomes; and Vitor Haubert for your time to talk with me. And to all the coffee professionals who have given me an interview since 2013. I learn a lot from you all!

KEEP THE FIRE BURNING

fogo baixo (low heat) newsletter is an initiative of journalist Flávia Schiochet and financed by her readers. All the essays, interviews, and extra editions will always be available for free, and you can read (or read again) on the newsletter archive.

Consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work for US$ 2 a month or US$ 20 a year (at the current conversion). Our next online meeting will be on Monday 21 February, at 5 PM (GMT-3 / East UTC-3), and we’ll talk about working conditions in the hospitality sector (in Portuguese). Supporters have a 10% discount in all courses taught by me and also nominally public acknowledgments at the bottom of all editions.

Spread the word:

NA: I made a wordplay when I wrote "próprio café", which can be read as the "proper coffee", as a way of preparing it the right way and investing in those expansive courses; and also read as "own coffee shop", because in Brazil "café" means the beverage but also the place where you drink it. So it would sound more like "your own coffee shop/coffee".

NT: Pão de queijo is an extremely popular snack all over Brazil, inexpensive and easily found in bakeries, supermarkets, and cafeterias. It’s a sort of baked cheese bun, made of cassava starch (polvilho doce) and/or fermented cassava starch (polvilho azedo), eggs, milk, fat, and cheese – preferably the saltier-but-not-so-hard-types, traditionally the minas meia cura or minas padrão. The different ratios of polvilho doce and polvilho azedo used in the recipe results from a more soft gummy compact pão de queijo to a thicker shell, dry and hollow version.

NT: SENAC is the National Service of Commercial Learning, a private entity for public purposes focused on providing professional education at all levels, all over the country.

NA: Another wordplay in Portuguese: "justo" can mean fair or tight, so I chose the word fit.

NT: Working less / everybody working / producing what’s necessary / distribute everything

This is a great piece, Flávia. The disparity between the wages for a skilled barista and all that they are required to do, not to mention the price of the coffee that is needed to just open the door to a business, is not fair. I agree with "Working less / everybody working / producing what’s necessary / distribute everything."