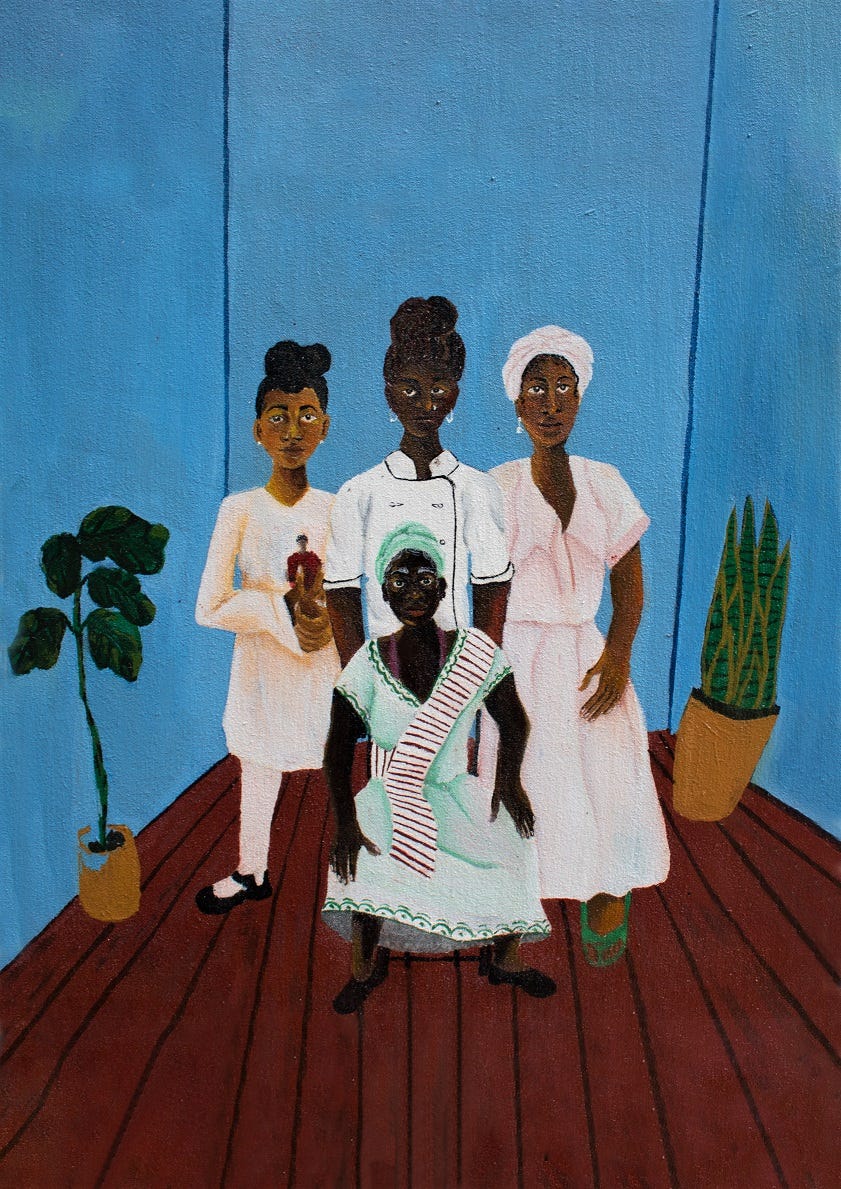

[interview: Taís de Sant'Anna Machado] "chef’s image is built in counterpoint to black maidservant cook"

sociologist analyzes three centuries of black woman's work in food, from the forced enslaved labor to the delegitimization suffered in today's restaurants

this issue was translated by Luciane Maesp 📧 luciane.maesp@gmail.com

clique aqui para ler em português

[⚠️ note: this edition contains affiliate links, which means that I receive a tiny commission if you purchase indicated books 🙃]

In 2010, the recommendation of removing Monteiro Lobato's1 "Pete's Hunting" book from the PNBE2 was understood as likely censorship for many sectors of society – including for one African literature in Portuguese language professor. I remember the uncomfortable feeling of reading the excerpts of the book quoted in the news articles and seeing opinions in favor of keeping the 1933's book on PNBE "because at that time most people thought that way". For a fact, some forgot to consider that it was a white majority thinking.

What was not on the public discussion's agenda in the 2000s and early 2010s was that Monteiro Lobato was an avowed eugenicist – he believed that some people were better than others due to some supposedly existent hierarchy between genetic, physical, and mental characteristics to value human beings.

In 1914, Lobato sent a letter to a widely circulated newspaper in which he said, among other things, that the "caboclo" was "unadaptable for civilization"3. This letter got published in the articles section, and he started writing publicly more frequently since then. Almost a decade later, the so-called author dedicated himself to children's literature – openly racist and with a very colonial subtext, to say the least. All of his writing stems from the same ideology, and it's easy to realize it when we make an effort to analyze it far from nostalgia, and not get carried away by the technical quality of his writing and textual composition. Just like color, erudition is not synonymous with moral virtue.

At the beginning of the 20th century, eugenics, the hygienist movement, and the "developmentalist" health walked side by side and shaped that time's public debate: medical advances, such as the vaccine, were reported on news commingled with events like the "Eugenic Baby Contest". Despite being blatantly present in this children's beauty contest, the pro-eugenic movement had (and has) many faces, whose actions and speeches are not always easily recognized. There is an elaborated material to understand the presence of eugenist discourses in the Brazilian public debate on the first season of Pelo Avesso podcast [Portuguese only], which precisely explains the arising of the eugenist movement until the disguise and never-eradication of this white supremacist ideology in Brazil.

Thinking about the complexity and disputes that make up the political field since the human being has organized into society, supporting Lobato's work nowadays goes from naivety (as I once believed it would be) to conniving. The workpiece, of course, could be edited with critical notes to contextualize the reader in a cross-disciplinary study involving History and Literature. Would this be a smaller effort than editing new books, by new authors, more plural, and that talk about today's society?

I have neither expertise nor education to analyze the possible impacts of removing Lobato's books of scholarly content in Brazil. However, I can see the effects one of his characters had on creating a stereotype of a black maidservant cook.

Thus, I expect you to read this low heat's month interview aware that the eugenist mentality (most of the time discreetly) led the public debate in the 20th century: whether cultural production, economic privileges maintenance, and the Brazilian colonial elite minds, who always had plenty of space and echo on the traditional media vehicles.

The first time I wrote down Taís de Sant'Anna Machado's name was in August of last year while interviewing Lourence Alves. I heard from Lourence that Taís' doctorate thesis was an academic milestone. I also heard that, just like Lourence, Taís is one of the researchers that is analyzing the world through a black epistemology, which articulates different subjects to investigate issues that were almost always treated from a distant perspective, where the "ethnic" was always seen as an object of study, and not as a knowledge-producing agent.

Taís holds a Doctor in Sociology from Brasília's University (UnB). In her thesis named "A foot in the kitchen: a socio-historical analysis of black women's culinary work in Brazil''4 she bethinks the work of black women in the kitchen between the 18th and 21st centuries, from cook Esperança Garcia to chefs and professional cooks of today – who remained anonymous to protect them of retaliation. Taís presents the working conditions in the kitchens and the different ways these women found to resist and act, despite facing disrespect, day after day, for more than three centuries.

This academic work will be edited as a book, and its content adapted to a less academic language. Regardless, Taís' text flows very well, even for the lay reader. "I took care about the language when writing the thesis because I want everybody to read it. It's an invisibilized history that has to do with most Brazilians", she said. Part of the 305 pages of the thesis will be synthesized in less space, and the book is expected to be released in the second half of 2022.

Taís talked to me by phone for about an hour and a half. You can read below the main excerpts of our conversation, edited and organized for better comprehension:

You open your thesis with a chapter that narrates the change in perspective you had when your interviewees showed that they'd prefer to emphasize their achievements rather than publicize the prejudice they suffered. Reflecting upon the authorial cuisine and in the proposal, these women present to the world, what histories these chefs you interviewed tell through their gastronomy and dishes? What are they proud of creating?

How interesting, no one asked me about it before! There's not much of it in the thesis. My work isn't a recipe compendium, as many people think. It would be great to have the screening of these recipes without the generic "African" or "ethnic" labels, as to how everything that is not French or Italian is labeled. But this wasn't the objective – the focus was the work in the kitchen.

As an interviewer, I see different contributions and paths. These women are impelled into a straitjacket of what they can cook, of what white people want them to cook, so they're very pushed to African and Brazilian cuisine.

As authorial cooks, they are diverse. There's one that's the queen of French techniques. There's another one who is "god-forbid" to make ethnic food: she wants to be contemporary and make fusion cuisine, to cook from references and ideas that pop into her mind – just like the classic white male chef that comes back from Thailand incorporating Thai ingredients in his dishes. Some of these women who cook with African influences have references from many regions and countries of the continent. There's also one that cooks Brazilian cuisine with wild edible plants.

Many of them have to leave their authorial repertoires to cook what people order from them. They said: "I know that [African and Brazilian cuisine] is what people expect from me, but if I don't, who will do it? A white chef?" These women have a lot of practical experience and circulate through many possible repertoires.

How do female black chefs and cooks evaluate and relate to those stereotypes of the quituteira or even of the cook that only knows how to make ethnic food, or to execute someone else's menu?

Being seen as a quituteira5 or a black maidservant cook is one of their biggest frustrations. In the third chapter, I discuss that these women, either as professional cooks or chefs de cuisine, are in non-places. It's complex to understand the entrapment of the black woman in the kitchen, where she isn't supposed to be the chef, the first or second cook. She's expected to be the assistant or dishwasher. So, they've been occupying places where they "shouldn't" be. When we see the history of gastronomy from a racial, class, and gender perspective, the chef de cuisine's image is built in counterpoint to the black maidservant cook. The chef has to be everything that "she is not". Yet, when you see her as a maidservant, you won't see her for what she is.

Bianca Briguglio granted me the interview she did with Benê Ricardo [page 151], who passed away in 2017. Benê was the first female graduated chef in Brazil, and in this interview, she talks of all kinds of delegitimization and boycotts she suffered in professional kitchens. There were episodes like the kitchen staff putting shredded glass in a tomato sauce she was about to serve: an attempt to criminalize her. There are all sorts of stunts that mean "you don't belong here, you gotta get back to another job".

There are many types of harassment: your suppliers don't recognize you, the customers don't believe you're the chef. It undermines your everyday life. Nobody sees them as authorities. These women are in places that they weren't supposed to be. They say: "why do they see any white female chef as a chef, and see me as Aunt Nastacia?"6

Stereotypes such as Aunt Nastacia's, whose repertoire is about playing a role, and not thinking, belong to a project of a nation that slots black women in minor and subordinated places in a violent way – and this kind of work keeps the country running.

It is not by chance, it's intentional: black women imprisoned in these places uphold workforce prices for domestic work at a bargain. It's a project of white supremacy, of violence. It is at the core of the chef de cuisine definition: a role that wasn't meant for these women, but they are fighting to occupy it.

You say that, even without sounding combative and militant, black women used kitchens as a space of resistance and action, something little considered by common sense or even by the academic environment. Could you exemplify how black female chefs and cooks have been articulating agency and resistance in the kitchens over the centuries?

Kitchens are extremely racist environments. The mere presence of these women, their insistence on occupying these spaces as chefs and cooks, is itself agency and resistance. Racism, sexism, and classism operate in different ways and women's actions stem from the breaches they find. Those who could study in international courses or have worked in better workplaces, manage to stand up against some structures and bring other black professionals to these spaces. Those who couldn't access it because of a racist structure that affects their income and opportunities, have to give in on many points.

I had to leave out of my thesis many things I heard from these women because I could put at risk their professional careers. If [as a cook or chef] you talk about these acts of violence, you get sanctioned, and you'll be seen as a troublemaker.

There's also networking between them, an attempt to have mobilization, an openness for some level of discussion about racism against black people. These women share opportunities among themselves, set up projects, and fight for certain food repertoires and their authorship (usurped by white chefs). They strengthen quilombolas7 and indigenous communities so they can also claim ownership of their repertoires. Gastronomy is a very predatory field to the knowledge of native peoples, quilombolas, indigenous peoples, and terreiro8 populations.

It's important to me to point out that there are other mains of resistance because black people need to access them. The sanctions [against those who stand up for their rights and needs] are very tough, and fighters can even lose job opportunities like in every labor market. This fight is set in a field made for white men, in which the recognition policies were made to award them. We know that some famous chefs don't hire women and have no shame in saying it.

When you're a woman seen as a troublemaker, you might not get a job, and it means having no subsistence. Then, less direct and more silent resistances are required. That's why my thesis harps on this point: there is a long history and tradition of resistance which begins with a petition letter from the cook Esperança Garcia, in 1770 [page 45]9.

The angle from where you see the black women's work in the kitchen is still not very common in the academy. Even you chose this perspective after a few years of doctorate studies. What would you highlight as possible research that stems from your academic work?

My thesis is a water drop in the ocean. I focused on only one group in the kitchen, but it's essential to understand the relevance of critical thinking on food.

People lose themselves in this statement that food is culture, but not always culture is something good. It can be violent, as the thesis shows. Eating habits and recipes are always cataloged as if they exist spare from a structure of power, violence, and economic exploitation.

Black women [who work or worked as housemaid cooks] have always been put under impossible survival conditions in the kitchens. While white families had sumptuous feasts, the black maid's families were in famine. Sometimes the payment was the leftover food.

This perspective and critical vision work for every other research on kitchen work. It's an invitation to look at other things: how whiteness is seen as a model, how white people "dominate" cooking repertoires that aren't theirs and behave like it was somehow natural – as if they could do everything and understand everything.

In my research, I'm toning gender and race. It's important to think about how a black female chef will have an experience that is not "only" worse but different. Their connection with housework is worse. The kitchen is also a space of outrageous violence for white women, but it is an entirely different experience. Few studies are thinking about gender and whiteness, about white femininity. There are several possible paths to enlarge and discuss this point of view.

Your research brings many oral reports and realities that weren't written, documented, and validated by the academy. How did the examining board and your peers evaluate it?

I don't think that my work is flawless. I know I lost sight of certain perspectives because it is a pioneer work. Whoever comes after me can develop critical sight on it, we can all think critically about the kitchens' history. I'm not a historian, and I may fail [as using Oral History methods]. To talk about a history that was intentionally erased and made invisible means that, to uncover it, you have to look for it in other sources with other methods. It's a social analysis and I'm embracing all kinds of records: obituaries, letters, biographies, personal diaries, file registers, movies. I am looking for feminisms and black perspectives, Brazilian and American.

Because of the character of what I'm studying, I have to consider different sources. Also, what I make from this black perspective and what's in my theoric-methodological basis is the definition of undisciplined research. The theoretical canon of Sociology doesn't handle what I'm talking about, nor does History's canon. That's why I have to make this amalgam, to be able to talk about what I'm studying by articulating different fields.

Every research is fated to be limited, and I think there's no other way to do it. I'm making a methodological path as I go along. I didn't get criticized for this in the examination board, but I wasn't worried about attending a disciplinary rigor of History or Sociology – I was concerned about treating those black women's history and the way they wanted to tell it respectfully, though. I don't give voice to anyone, I evoke. I intend to serve as an echo of these histories that were silenced and to make sure people can easily access them.

In the post-slavery abolition, the public space, being on the streets, and street food were seen as a black domain. Then, restaurants and hotels inspired by European hospitality came up and took the public thoroughfare. What did this displacement and marginalization cause to black female cooks' work and the population's eating?

The post-abolition process is tough itself because black people got free from slavery without any reparation. It was an extinguish and decimate project: there were a gamut of attempts to whitewash the population; land policies to impede land access; the impairing of education access; policies to criminalize black female cooks' work on the streets.

Impeding access to certain income-producing spaces is part of this project. So, the civilized white European country [as Brazil imagined itself] made black people's living conditions, which were already grim, even worse.

At the same time, cities depended on black labor. Taking black female cooks off their street work made the precarious situation even poorer. The food supply chain depends on the food circulation in the city, fairs, and on-street food, which has always been very common in Brazil. You'll always find a black woman with her food stall. They were removed from some city spaces, sometimes taken by force of spots that were getting urbanized and Europeanized. But they never leave the street work, these women just go to other places in precarious conditions – the streets remain black territory despite all the criminalization of this work. I quote in my thesis Bruna Portella de Novaes’ dissertation, "Whitewashing the black city: street work management in Salvador at the beginning of the 20th century", which is great research to think about this question, especially in Salvador.

What can you say about the difference in the opportunities between the city and the countryside that black female cooks could find in the post-abolition period?

The city means the possibility of accessing other jobs or other bosses. These women are astute, they can see how the structure above them operates and then find gaps to occupy certain spaces. The idea that black people are a subservient workforce is a whites' invention. They were always looking for other jobs, with better treatment, better wages, better labor conditions, to ease their child's care – things that may seem minor changes, but were often very significant in their daily life.

In the post-abolition, many women got stuck to the families that enslaved their families, and the blacks sometimes felt like they owed something to the whites. Ms. Risoleta went to work in the city with the daughter of the man who enslaved her father [page 107]. She, at 8 years old, was taught how to work. In the countryside she had less possibility of transiting and poorer living conditions, so she went to the city. There, she also works for a family, and then she realizes she can work in the newborn public hospitality structure of São Paulo. There were the big hotels with chefs de cuisine, and the boarding houses which had small restaurants that also served wealthy families.

These women are always moving: there's forced migration due to the people's traffic, then an obliged migration to get better living conditions. The labor conditions are far different between the city and the countryside, then the rural exodus happens because they needed it and not because they wanted to.

Cities were spaces to look for more opportunities, as in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. You go around and look for new conditions, which sometimes was a better treatment or the non-necessity of sleeping in the workplace.

In the cities of that time, the work in public space kitchens had more "autonomy and freedom" (between many quotation marks) than working in private kitchens?

I don't want to make general comments. It changes by case. Kitchen labor conditions were very unhealthy, it was considered a humiliating job, full of physical and sexual violence – it was not rare for those females workers to get continuously raped. There were all sorts of tortures, and people had to sleep on the kitchen floor. Working in the kitchen meant having the worst living conditions inside a house. There's a story where the proprietor says that she would put in the kitchen the enslaved she liked the least. The first part of my thesis is named "Kitchen was not a place for people" because it was portrayed as a place where everything filthy happened.

Moving from the private kitchen to a public space kitchen means that now you could be with your children, have a partner, visit your family. You'd have a better income and a less violent and humiliating life. We can't generalize it, though: the streets may not be understood as a space of complete freedom and tranquility because it was also a space of physical and sexual violence. Women on the streets were frowned upon, and the work routine was also very strenuous.

The kitchen work is extremely exhausting at any time in History.

Working in the public space, maybe you'll manage to have a place to leave your stuff, but mostly it's an itinerant job where you have to walk miles carrying a heavy basket over your head. Even with the difficulties, it was better than being under one's yoke, being humiliated, suffering physical violence, and being at the risk of not being paid according to the agreement.

In "Bitita's Diary", Carolina Maria de Jesus shows that she was willing to enjoy her youth, but she didn't have time. It was a huge achievement for black women to go to balls. Ms. Risoleta reckoned that she would go six months without seeing the street. There were many layers until these women got the conditions of being able to be people, manage to minimally live their lives.

The balls are a present memory of the beginning of the 20th century – but they weren't a reality for black women, who were confined and imprisoned in exhausting work shifts. This kind of work was essential for upper-middle-class life maintenance. And it meant depriving people of being people.

A black woman in a precarious and strenuous job is the condition needed to support white middle-class people's lives. The pandemic showed the deepening of something that seemed stuck in the past but comes back now with full force: the project of non-guarantee of basic rights, bringing the past alive again. The way the pandemic has been managed [in Brazil] is a genocide of black and indigenous people – it hazards lives and increases inequity, impoverishing people and putting them in this kind of position again because there will always be demand for domestic work.

To read articles and check on other interviews with Taís, follow this thread on Twitter.

PICK UP WHAT YOU WANNA READ

To choose which sections of the low heat newsletter you'd like to receive in your inbox, click here and select the checkboxes that interest you. Those who read only the English version can no longer receive the Portuguese version by checking only the [EN] LOW HEAT checkbox. If you want to receive all the editions, in Portuguese and English, check all the checkboxes, as on the image below:

SUPPORT LOW HEAT

This newsletter is an initiative of journalist Flávia Schiochet and financed by her readers. All the essays, interviews, and extra editions are always going to be available for free, and you can read (or read again) on the newsletter archive. If you liked this content, please share:

If this link came to you by a friend, consider subscribing! Every month, two pieces are published: an interview and a slow-cooked essay on food, cooking, and gastronomy.

Consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work for US$ 2 a month or US$ 20 a year (at the current conversion).

NT: Monteiro Lobato (1882-1948) was a Brazilian writer and journalist, most known for the Yellow Woodpecker Farm (Sítio do Picapau Amarelo), a fictional universe of children's fantasy books, which were adapted for movies, series, animations, comic books, music, theater plays, games, and more.

NT: The National Program of School Library Collection (PNBE) is a public policy that distributes all kinds of books in particular and in public schools. This policy encourages the existence of libraries; the expansion of their collections; reading habits; and access to culture.

NT: In colonial Brazil, caboclo was the result of the miscegenation of white Europeans and Brazilian indigenous parents.

NT: “Um pé na cozinha” or “one foot in the kitchen", is a racist expression to say that someone has a black origin. During the slavery period in Brazil, black women could only be in the colonizer's farm owners’ main house (casa grande) as enslaved cooks/housemaids. It also refers to the stereotype that women are good cooks.

NT: In the 19th and early 20th century, as slavery got disused in Brazil, black women had an important role in feeding the workforce and students, buying the manumission of enslaved people, and making their independence by working as quituteiras, by cooking and selling quitutes – sweet and savory delicacies ready-made or assembled on time, mostly recipes from African and orishas cuisine. Their tiny stalls (tabuleiros and balaios) in the city's streets easily became meeting points for black people, where politics, food, business, family, and leisure occupied the same spot.

NT: In the “Yellow Woodpecker Farm” universe, Aunt Nastacia is a black servant and cook who works in Mrs. Benta's farmhouse. While Mrs. Benta is the white literate grandma with European features who love embroidering, Nastacia is the portrait of the Mammy caricature: an assistant, faithful worker, talented cook, kind-hearted soul, who knows native folklore.

NT: Quilombolas are the people that live in quilombos, hidden spots in the forests where the enslaved that could run went to live during the colonial period in Brazil. Nowadays, the quilombos house mixed ethnicity, but keep sharing African ancestry. They form a community that stands up against the urbanization process and for a simple life in contact with nature.

NT: Terreiros are the traditional temples of African-matrix religion practices, such as umbanda and candomblé.

NT: There’s an academic article and a children’s book about this letter, both in English.