#2 | broken rice

on virtual indignation, public food security policies, and honest arguing

Hello again.

I'm late on my schedule to translate my articles to English, so it's likely you receive two more emails until Tuesday, August 31th. I know it's a lot, but on September everything should go back to normal. fogo baixo is a monthly newsletter, and I'm trying to increase the frequency to be a biweekly one from October on.

If you received this newsletter from a friend, consider subscribing. :)

Curious about what fogo baixo means? Click here.

clique aqui para ler em português

A WATCHED POT NEVER BOILS

what could have been (but was not)

For this month's piece, I was writing a personal essay about fine dining. I wanted to explore how the pandemic of Covid-19 made me realize the knot that made me so close to haute cuisine is a loose one.

The impossibility to eat out – either by city decrees or because I don't feel secure at all – and knowing that the budget can get tight at any time, there is no way to keep myself really up to date on what new establishments taste like, or try the seasonal tasting menu from a renowned restaurant, etc, etc. It upset me a lot at the beginning of the pandemic, around April (I am a precocious sufferer), and I had an absurd identity crisis.

More than one year later, I finally absorbed the impact and started asking myself: why am I still interested in a niche that is serving fewer and fewer people in a country where the most recent discussion is about people having to buy broken rice?

In July, Brazilian Twitter made a single image go viral with countless variations on the phrase "the industry is selling broken rice, an animal feed, as an alternative to rice". I engaged readily. Since I was questioning my interest in fine dining while missing a six-course menu, that was the perfect time to abandon the piece where I inevitably would write about the natural sweetness of pea and stuff like that. Haute cuisine started to sound like a frivolous theme for a Brazilian journalist to write about.

That was the beginning of my essay's journey into the draft drawer. I noticed that I was too close to the discomfort, and could not look at it coldly enough to write about it without explaining myself every two paragraphs.

And, well, I was wrong. Fine dining is not serving fewer and fewer people. That is not what I empirically have heard and seen.

Between June and July, on sunny walks to distract my mind, I came across two friends. They work at different places, both contemporary restaurants from nationally and internationally renowned chefs. I think I have interviewed these chefs a dozen times each (if not more) since 2013 when I started as a gastronomy reporter in Curitiba. Eating in their restaurants, however, err… I must have gone three times at most.

What I heard from my friends is that the work remains intense. What changes is the number of customers that the municipal decrees allow to have in the restaurant's salon, which varied between none and half of the capacity in these almost 18 months of the pandemic.

The curious ones, like me, are gone. The not-so-low-and-not-so-high middle class, which I belong to, keeps its standard of living, I know. We had to reset the gastronomic antics we allowed ourselves from time to time to celebrate and feel the taste of luxury in our taste buds. But we are still well fed and comfortable in our houses.

The true fine dining customers remain with their untouchable perks, making lines and filling reservations. People who routinely have dinner in luxurious restaurants twice or three times a week have not been deprived of anything in recent years. They go on eating foie gras, enjoying fresh Italian summer truffles, and ordering bottles of four-figure wines. They are surely not counting coins. The increase in the price of these ingredients does not make their consumption unfeasible, does not increase national hunger, or even brings down a sector of jobs – unlike rice and beans prices.

After realizing that, I put my draught in the freezer. I could not deal with it back then, and I suppose it will be like this for a long time.

[ok, let's get on the newsletter's subject]

THE BROKEN RICE MATTER

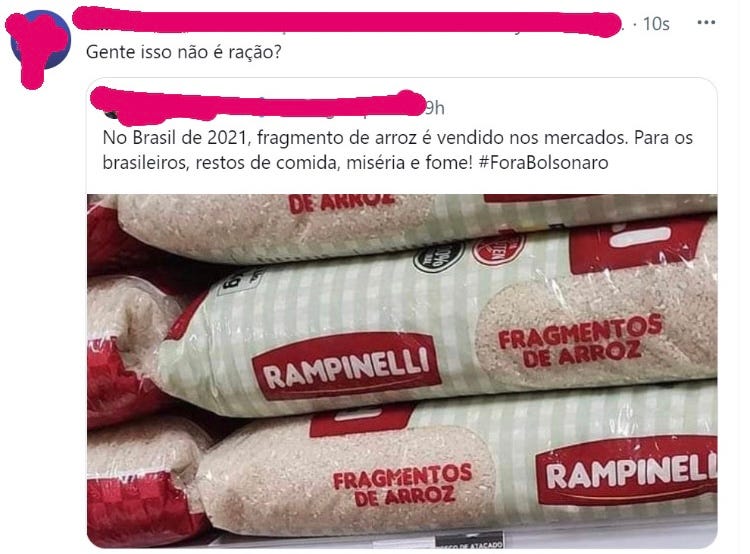

Two tweets published in early July got me convinced that abandoning the personal essay was the best thing to do. One of them shows a woman crying during an interview at the supermarket. The other one was a picture of a five-kilo-package of broken rice – or rice fragment, as it is also called. The profile I embedded was deleted, but I'll leave a print from a similar tweet here:

It was shared to exhaustion, in so many different profiles – deputies, nutritionists, journalists, influencers, and so on – however, no one published a single line about in which city, supermarket, or even the date the picture was taken.

Data analyst Júlia Jacob, a friend of mine, drew attention to another detail: if this lower value product were an option for feeding vulnerable populations, it could be in popular supermarket chains and as an option, for example, at Armazém da Família, a public policy in Paraná in which products are sold for an average price 30% lower than those registered. We did not find the broken rice listed as an alternative in July. I took a walk at a popular supermarket near my house and did not see a single package either. Researching for online purchase, I found a brand called Romãozinho for sale only on Angeloni's chain for R$ 3.65 (1 kg).

According to Rampinelli Alimentos, the picture was taken in a GPA's store (a group to which belong Pão de Açúcar, Extra and Compre Bem supermarket chains), to which Rampinelli sold more than half of its production of broken rice: 64.5% in 2020 and 72% in 2021 until July.

GPA sent me a note:

“The Group informs that it is not possible to identify if the photo was taken in one of its stores and, also, that the product in question is no longer purchased by the company, but eventually there may be small quantities of the item in a store.”

does broken rice replace the integer one?

Broken rice is a by-product of rice production – either white or parboiled rice. Broken grains from different sizes are taken apart in the last stage of rice processing. Broken rice is cheaper because it differs from the Brazilian's preference for integer rice grain with uniform color. Eating ground or crushed cereal should not sound like a scandal; polenta is an example of this.

Type 1 rice has unquestionable – materially and symbolically – value to Brazilians. That is why the picture that shows 15-kilo packages of broken rice became the symbol of impoverishment in Bolsonaro's government. Many tweets state that broken rice was now part of Brazilian meals replacing type 1 rice, and some websites and blogs published articles reverberating the statement, without checking this so-called fact.

[well, some days later, Projeto Comprova checked it, and I understood I was not mistaken]

I asked Raquel Canuto for help; she is a professor in the Nutrition department at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. I wanted to know if she thought I was losing sight of something when writing this piece.

“The nutritional value of broken rice does not necessarily decrease, but what caused this indignation is people's lack of access to a daily feed intake. It symbolizes the lack of access to basic,” she told me.

A repercussion like that would be unlikely if our present and past governments were doing their role and keeping public stocks supplied as a strategy to assure food security. The volume of rice stored has been decreasing since 2012, but it was from 2015 that it began to decline rapidly.

The lack of strategic stock soared the price of rice in 2020 and kept it high in 2021 because Bolsonaro's government expects the price of staple food to be adjusted by the law of supply and demand.

[I hope it is unnecessary to explain why this is degrading reasoning]

Júlia summed up the context: not only the National Supply Company (Conab) is impaired, but the unemployment rate of 14.7% is the highest in Brazil since the beginning of the historical research series in 2012. The Brazilian's eroded purchasing power is also due to the inflation (rates that remind us from our 1990s' economic); the wage adjustment being equal to or less than the inflation; and to another dismantling of guarantees, such as the social security reform and the tax policy that makes the populations with less purchasing power pay more taxes.

There is also the price of animal protein, an ingredient that is once again unknown to Brazilians. “There are more perverse things [than the possible replacement of rice with rice fragments] that have been going on for a long time, such as, for example, access to meat. Poor people don't eat meat, they ask for bones and fat and cook with them to get some flavor. The meat by-product is eaten every day, such as nuggets and sausage, made from animal remains and crushed skin and bones because they have no access to filet mignon or steak,” said Raquel.

We agree on the point that, even if broken rice is a by-product, it is still food, just as cornmeal and a broken chestnut are – and not like sausage. So I went checking on how important broken rice was commercially for Brazil and if its volume could replace rice in Brazilian's diet.

broken rice, not rice bran

In the statistics provided by the Brazilian Association of the Rice Industry (Abiarroz), the export of broken rice in the first half of 2021 was similar to the same period in 2020, around 167,000 T, and the main buyer countries were Senegal, Netherlands, Gambia, and the United States. However the coming-in of broken rice was higher in the first semester of 2021 than the same period in 2020: 5,900 T versus 3,700 T, coming from Paraguay and Uruguay in 2021 and Paraguay, Uruguay and (very little) from Germany in 2020.

There is no information about the destination of these rice fragments imported by Brazil, but the volume would not be enough to replace integer rice for human consumption – the Brazilian domestic consumption of rice is around 11 million tons a year. For agribusiness, thousands of tons are crumbs compared to the volume and value of other commodities and integer rice itself. In the Sectorial Chamber of Rice (Câmara Setorial do Arroz in Portuguese), I did not find data on the internal consumption of broken rice.

The food industry can ground broken rice until it becomes flour and then turns it into baby food, cookies, or gluten-free pasta. It can replace corn in the animal feed industry or its starch used to initiate or accelerate the fermentation as in beer brewing.

A booklet published by Embrapa in 2013 explains how the industry uses three by-products of rice processing – the broken (fragment), the bran, and the husk:

“Broken rice, most used for the production of animal feed and beer, can also be used to produce a variety of products such as rice paste, vinegar, cookies, flour, starch, and as a substrate for alcoholic fermentation to obtain ethanol.

The bran (which contains, on average, 20% of lipids, 14% of proteins, in addition to good levels of vitamins and fibers), in Brazil, is used mainly as a component of animal feed, but it can also have many applications, as in edible oil extraction and the production of flour and protein concentrate.

The husk has no food application, although it has potential for use in various areas.”

Commonly bought to be prepared as dog food, broken rice is recommended for this purpose because it is cheaper than integer rice, and dogs do not mind its creamy texture. Also, Rice Technical Regulation (Regulamento Técnico do Arroz in Portuguese) allows up to ten grams of foreign matter per kilogram for broken rice – the maximum weight is one gram of foreign matter per kilogram for type 1 rice.

The information for both nutritional tables (cooked integer white rice and raw broken rice) are similar. I did not find nutritional information on the cooked rice fragment for a more assertive comparison, but it is known that a broken or ground cereal facilitates the release of starch during cooking, and that is why it is proper for creamy preparations such as when you use cornmeal to prepare polenta or to give texture to a broth or soup.

“Soups and creams are traditional meals made with broken rice in South Brazil,” told me by telephone Juliana Rampinelli, a partner at Rampinelli Alimentos. The company has an office in Forquilhinha, a municipality next to Criciúma, in southern Santa Catarina, and sells 30-kilogram bales to supermarkets in the region at a price equivalent to R$ 2.56 per kilo for rice fragments, while white rice type 1 would cost the equivalent of R$ 3.26 per kilogram.

Rampinelli has been producing broken rice since 2016, when they opened a factory in Eldorado do Sul (RS), and has seven rice types in their portfolio, in addition to selling rice fragments, rice flour, and rice cookies. Juliana gave me the year-to-year sales increase – an average of just over 5% per year between 2016 and 2020 – and broken rice share has averaged 0.5% in the company's sales since 2016. “We did not observe a sales increase of this product,” Juliana emailed me later.

Even though I know that all the controversial discussions on the internet disappear in few days, I still tried to see if the supply of rice fragments had increased in any region of Brazil.

I wrote to the Brazilian Supermarket Association (ABRAS) to ask if it would be possible to survey the purchase of rice fragments and integer rice by supermarket chains from 2017 or 2018 (yes, I know it was a lot to ask). ABRAS denied being able to help (as I presumed).

Rice and beans that feed Brazilians come from family farming, so I researched for rice fragments at the Family Farming Window's archive, a part of the Secretariat of Family Farming and Cooperativism (SAF). There is only one broken rice package registered, while there are 65 entries for integer rice of the most varied types.

Since it is impossible to have rice production without broken grains, I dare to infer that producers prefer to sell rice fragments to the food industry rather than retail. SAF told me to speak with the Sector Chamber of the Rice Production Chain, but I did not get any reply until the closing of this article, in the late afternoon of July 26th. Though in the documents available on the Sectorial Chamber's website there are many projects to encourage and disseminate the use of rice flour, though.

I wrote to four big rice brands to ask them what was done with the production fragments – whether they are sold to the food industry, used to produce other items in their portfolio, or whether they are packed for retail. Camil's press office informed that the brand does not want to talk about this subject. Tio João's press office returned saying that the manufacturer, Josapar, did not record any change, without providing details on volume, percentage of broken grains, or their destination. On August 2nd, a marketing spokesman from Arroz Urbano wrote me back saying that the brand uses part of the fragment as an ingredient in other items the brand produces and packages a part of it to sell on retail. The fourth brand did not respond at all.

The emptiness of public policies, the reduced income Brazilians are experiencing again in 30 years, and the escalating food insecurity are the reasons that rice is expansive. Either the integer or the broken one.

Hey, thank you for reading this issue through! 😊

That’s the second article I translate and it would mean a lot if you could tell me how I can improve my writing in English. Please feel free to email me: schiochetflavia@gmail.com

If you liked fogo baixo, please share it!